COVID-19 has forced most of the western world into lockdown. Business has

essentially stopped, but bills continue to come in. A business’s expense is

another business’s revenues. Once a business cannot generate revenues, it

cannot pay expenses, which impacts the revenues of another business which

cannot pay their expenses, and so on and so forth. What we are now

experiencing is akin to an automobile crash pileup, where the lead car brakes

suddenly and all the cars behind crash into the one ahead of it.

- Buffett, October 20084

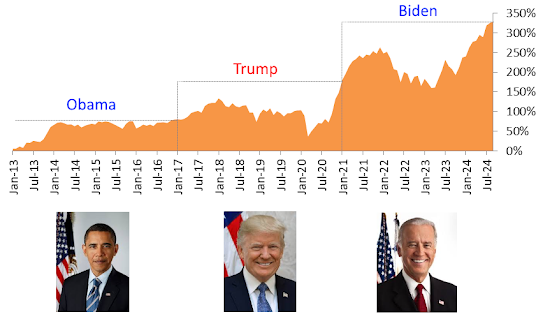

To put it bluntly, this is what we have been waiting for. Nearly every quarter, I lament the endless bull market that has made

outperformance so difficult for value investors like myself. Sure, we’ve

experienced some harrowing dips along the way, but all have snapped right

back within a few months, never once really threatening to derail a

decade-long bull run. But now, in a violent fashion, the bull has

definitively died and we will enter a deep recession. Finally.

I began my investing career in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. I

experienced first-hand how bear markets are where true wealth is created.

Bear markets wash out the weak. The weaker companies, the weaker investors,

they are forced to fold in an environment where consumers are more

discerning, where bankers clutch their purses tighter, where capital is

hyper averse to risk. The grittier ones survive, and when things inevitably

bottom and start turning upwards, they are there to reap the spoils, the

extra market share vacated, and emerge exponentially stronger.

Without a doubt, things look scary and terrible right now. When you open

your statement, you will probably experience a jolt of cold sweat, an

atavistic fight or flight response. This is perfectly normal, but let me

assure you, individual stock prices right now do not accurately reflect any

semblance of reasonable value. What they reflect is a fire-sale value. It

reflects that fear you feel, of scared sellers overwhelming buyers.

There is no reliable method to pick market bottoms during recessions, but

one saw is inviolably true: stocks always bottom well before the recession

is over. If you don’t stay the course and pull out to wait for rosier

economic indicators, you will miss out on massive gains. The graph on the

right shows the return on stocks from the bottom of each bear market until

the official end of each recession. Such returns average an astonishing 64%

compared to long-term annual returns of 9.8%5.

Another way to look at it is what that long-term annual return would degrade

to if you miss just a handful of the “best days” in the market. Missing just

10 of the biggest up days reduces your annualized returns by 2.7%. And

missing the 50 best days… you might as well just leave your money in a

checking account. Translated into dollars, if you invested $1 at the

beginning of 1992 and held until the end of 2019, you would have $13.66.

Missing the 10 best days nets you only $6.82, and missing the 50 best

reduces that all the way down to $1.31.

Source: Goldman Sachs Portfolio Advisory Group “Rebalancing and Market Entry

in Down Markets”; Bloomberg

According to data compiled by Charlie Bilello of Compound Advisors, -20%

bear markets occur, on average, every 4.4 years, -30% every 9 years, and

-50% every 20 years6. And yet, through thick and thin, stocks reliably

outperform every asset class in the long run. To enjoy long-term returns

that equity securities offer over fixed income, the price of admission is

volatility—sometimes mind-numbing, cold-sweat inducing, vomit-reflex

engaging volatility.

With that said, I will not put us in a position where we would risk margin

calls. In other words, we will always be net cash positive. In this

environment where prices gap up or down by double digit percentages with no

fundamental reason, anyone on margin could get involuntarily liquidated by

their broker. Enough money can be made with no leverage whatsoever, and

besides, careful use of options, hedged or covered or in-the-money ones

provide us with plenty of asymmetric return opportunities.

Why This Time is (Not) Different

What causes economic recessions? Traditionally, it is caused by an imbalance

between allocated resources (capital and labor) and resulting productivity

(profits). In other words, resources that do not produce profits. That

results in losses in capital and layoffs in labor. For example, dot com bust

happened because too many then-newfangled internet companies had no pathway

to profitability and yet sucked up large amounts of capital and labor. The

process of reallocating those resources into actual, productive endeavors is

what eventually digs us out of a recession.

In 2008, the financial crisis was precipitated by overinflated real estate

prices. Capital and labor poured into the housing sector, building more

homes and generating more mortgages than was needed by magnitudes.

Eventually the mortgages could not be paid, which led to foreclosures, which

drove down real estate prices, which halted new construction. The value of

mortgage-backed securities collapsed, which decimated the banks which held

large amounts of such securities, which led to a huge pullback in lending

activity, which caused the intense recession. Digging out of it required a

long and arduous process of reallocating the substantial amount of resources

previously dedicated to housing and banking.

This time, it isn’t the popping of an asset bubble that is driving capital

losses and mass unemployment. It is, instead, an artificial halt to

the economy. Instead of the invisible hand of free markets working to

reallocate resources from unproductive sectors to productive sectors, it is

a deliberate act of government policy to stop the spread of a pandemic. Once

the pandemic is under control, labor and capital will mostly return to where

they were needed prior to this recession. People will eat at restaurants

again. People will travel again, probably even on cruises again. This is

self-evident.

Compared to 2008, all the excess labor and capital left the housing and

mortgage industries permanently. People were buying houses they could not

afford by borrowing money that banks should not have been lending. Once that

popped, all those people needed to go find real jobs or start other

businesses that are actually sustainable. That created a prolonged period of

pain.

Another significant difference is the government’s response. Typically in

asset popping recessions, the government can be reluctant to step in and

bail out those who had wasted all those resources to no end. The right thing

to do is to let failure percolate, allowing painful memories to fester,

which will discourage the same bubble from forming again.

This time, since the government is directly “responsible” for the cause of

the recession, they are 100% incentivized to bail out whomever is necessary.

Already, over $2 trillion in stimulus have been approved to enter the

economy to bridge us past this pandemic. The Federal Reserve immediately cut

rates to zero and are committed to buying however much assets as necessary

to keep liquidity and credit flowing.

This difference cannot be emphasized enough: there is a bright green light

to print money and hand it out. If the $2 trillion is spent and we are all

still quarantined, they will print another $2 trillion, and it will again be

overwhelmingly bipartisan. Of course, the mechanism by which this payment

transfer is effected will inevitably run into snags as handouts of this size

have never been attempted before. But the incentive is there and it is

unwavering. That’s the key.

In this sense, we are experiencing a “crisis” more similar to World War II

than any other typical recession/depression/panic, where the majority of

citizenry and governments drop business-as-usual and participate in a joint

effort to defeat a common enemy. WWII, of course, was also the definitive

event that jolted the U.S. to slough off the Great Depression once and for

all.

***

How does this affect fundamental valuation of individual stocks? Without a

doubt, earnings this year for most corporations will decline dramatically.

But for most corporations, especially those that will survive this pandemic,

one or even two years’ worth of earnings is merely a blip in the overall

calculation of intrinsic value.

Intrinsic Value = Present Value + Future Value. PV roughly equates to

tangible book value, e.g. cash on hand, owned assets, working capital, etc.,

minus liabilities plus current earnings. FV essentially equates to the

accumulated future earnings stream from now until Judgment Day. What this

recession will impact most skews much more towards PV than FV. It will

certainly damage near-term earnings. It will surely damage the tangible book

value of banks who will have to deal with troubled loans. But if you own

shares in a company that will survive this crisis with no loss of reputation

or human talent or brand value – in other words, no loss on their ability to

generate profits in a normal functioning economy – it will continue to enjoy

a long and growing tail of future earnings stream. The importance of FV in

almost all typical going-concern operations far outweigh the importance of

PV.

Another way to think about this is to invert: which kind of companies are

unlikely to make it? It is companies that were already weak going into this

crisis. Companies that were perched on a tipping point and needed some good

luck to make it. Companies that are heavily indebted, whose intrinsic value

are actually held by bond holders rather than equity holders. In cases like

these, this recession will wash them out like every other recession. This

time would not be different for them.

The major holdings in our portfolio, if my assessment about this being a

maximum one to two year event with heavy and eager government support

throughout, should all comfortably make it to the other side. Their

intrinsic value may be nicked by temporary losses and mark downs, but that’s

why I purchased our shares at discounts to intrinsic value. In other words,

when I invested in our companies, I already baked in the certainty of future

recessions and unknown catastrophes. I have not and never will invest in

anything based on “blue sky” scenarios.

***

Some Extraordinary Commentary on a Specific Stock

The biggest contributor to our decline this past quarter was, by far, CIT

Group. CIT, if you recall, is a mid-sized commercial bank with about $50

billion in assets, which entered the quarter as one of our top two

positions. Shares went from $39.71 to $17.26 during March, but that doesn’t

even account for the true magnitude because in late February it traded as

high as $48 per share before hitting an intra-day low in March of $12.02 per

share. That, if you’re morbidly curious, is a -75% drawdown. Ouch. The KBW

Bank Index (BKX) over the same period of time (late Feb. to March lows)

“only” drew down -49%.

The proximate reason for the shellacking of bank stocks is the fear of

investors who believe we might be reliving the 2008 meltdown nightmare.

However, banks are dramatically different today than they were twelve plus

years ago. First and foremost, they hold much more “buffer” against losses

now thanks to an rule called Basel III. Basel III forced banks to keep more

capital on their balance sheet to defend against unexpected losses. How much

more? Prior to 2008, banks routinely borrowed up to 30 times their capital

base. These days, it’s down to around 10 to 12 times. This dented their

earnings power post crisis, but it has them well protected coming into this

pandemic.

Additionally, banks are now playing lead roles in recovery effort vs. being

lead villains in 2008. Government guaranteed loans from the $2 trillion

stimulus will be underwritten and distributed by banks to help businesses

pay their bills and debt. Banks can then securitize these loans, plug into

the Federal Reserve, and dump the credit risk onto the Fed’s balance sheet,

which may be able to accommodate up to $4 trillion7 in such guaranteed

low interest loans. This mechanism should theoretically act as a bridge for

companies who otherwise would default on loan payments to get to the other

side of this crisis intact.

With regards to CIT specifically, there were no fundamental reasons for it

to decline with such a velocity outpacing the rest of the financial sector.

The only probable explanation is their history, which saw them succumb to

bankruptcy by the financial crisis – perhaps institutional memory had folks

dumping CIT in fear of a redux. However, as I’ve explained in my annual

letters, CIT is a completely different beast these days. Back then, they

were encumbered by a mish-mash of random assets, including subprime lending,

manufactured housing loans, aircraft leasing, etc. They weren’t even a bank

holding company! Today, they are a legitimate, regulated, vanilla

nation-wide commercial bank with an investment grade balance sheet, pure and

simple.

Furthermore, as recent as 2017, CIT was required to undergo annual “stress

tests” administered by the Department of Treasury8. The stress test scenario

envisioned a prolonged, 9-quarter recession with double-digit unemployment

and a nearly flat yield curve. In such an environment, CIT would suffer

cumulative losses of -1.8% of assets, or just under a billion dollars9. It

hurts, but it is a fraction of the $3.5 billion discount to book value CIT

is currently trading at. In other words, shares are priced as if the losses

will be over 3.5x the severity of the financial crisis. This is not to

mention the fact that CIT is an even stronger bank today than it was three

years ago.

Don’t just take my word for it. In light of these facts, insiders acted

aggressively to buy stock on the open market. Twelve members of the board of

directors and the management team spent over $1.6 million of their own money

on CIT shares last month, with the two largest blocks coming from the CEO

and the CFO. In a nutshell, the very people who are evaluating the company’s

risk in real-time are the most bullish.

And so: I’ve been adding to our stake all the way down, which has

temporarily made our results look rather dour but has me quite excited about

the potential returns on the upside. I don’t typically disclose this much

detail about individual stocks in quarterly letters, but during this

extraordinary time, it is only fair to be transparent about my most

aggressive moves so you understand I am making my decisions with rationale

and logic rather than that four letter word h-o-p-e.

8 The requirements were changed in 2018 to only stress test banks with over $100 billion in assets.

To Sum Up

It is an extraordinary time to be living through right now, both as an

investor and as a regular human being. I am in awe of the might of humanity

aligning together against one objective: beat COVID-19. From the doctors and

nurses on the front line, to the restaurants, grocers and essential workers

working to feed us, from the scientists and researchers who have dropped

everything else to focus on this virus, to the career government employees

responsible for crafting policy and guidance that will help bridge us across

these tough times – heroes one and all, but individually destined to be

unsung.

Our companies have stepped up in kind, doing what they can. Our banks will

be front-line distributors of loans and grants that shore up business cash

flows and keep people on payroll. GM has retooled plants and leveraged their

formidable supply chain to build ventilators and masks that will literally

save lives. Dish is donating spectrum to T-Mobile and AT&T to ensure

there will be enough bandwidth to communicate on and even giving free Sling

TV access for 14 days to ease the burdens of quarantining. BlackBerry is

providing 60 days free access to remote workplace tools that have become

critical for white collar workers. Added together, the reputation of our

companies will surely be strengthened on the other side of this crisis.

Soon the infections will peak, and soon we will have antibody tests to

administer far and wide. Soon there will be targeted therapies that will

save a majority of even the highest risk cohort. And then, there will be

vaccines, and then it will be over. Although the timing is unpredictable,

victory is inevitable. I will never understand the pessimists who bet

against humanity and against America, those who may achieve a temporary

thrill when their contrarian bets pay off once per decade but spend the rest

of the time reliving past glories and hoping for future doom.

.png)

.png)